Once Upon a Time…

The Myth of Rationality – An Introduction to the Potential of Brand Stories in Brand Development

You can find the original post in German on my website: www.launch-point.de/es-war-einmal-das-maerchen-von-der-rationalitaet

If you have feedback, comments, additional insights, or ideas, or if you need support for your project, I’d love to hear from you.

"Brand storytelling?

That’s just a gimmick, a passing trend!

We prefer to rely on quality and facts."

I often hear statements like this. But it’s not that simple. Human decisions are more than just the sum of cost-benefit calculations. Behind every choice, every purchase impulse, lies more than pure logic. Emotions, experiences, and subconscious patterns subtly shape our perceptions.

When we translate our values into stories, products become experiences, and numbers turn into relationships. This creates a space beyond cold logic—a place where brand identity comes to life.

Why are facts alone not enough?

How does brand storytelling contribute to brand development?

What exactly is brand storytelling?

The Limits of Rationality

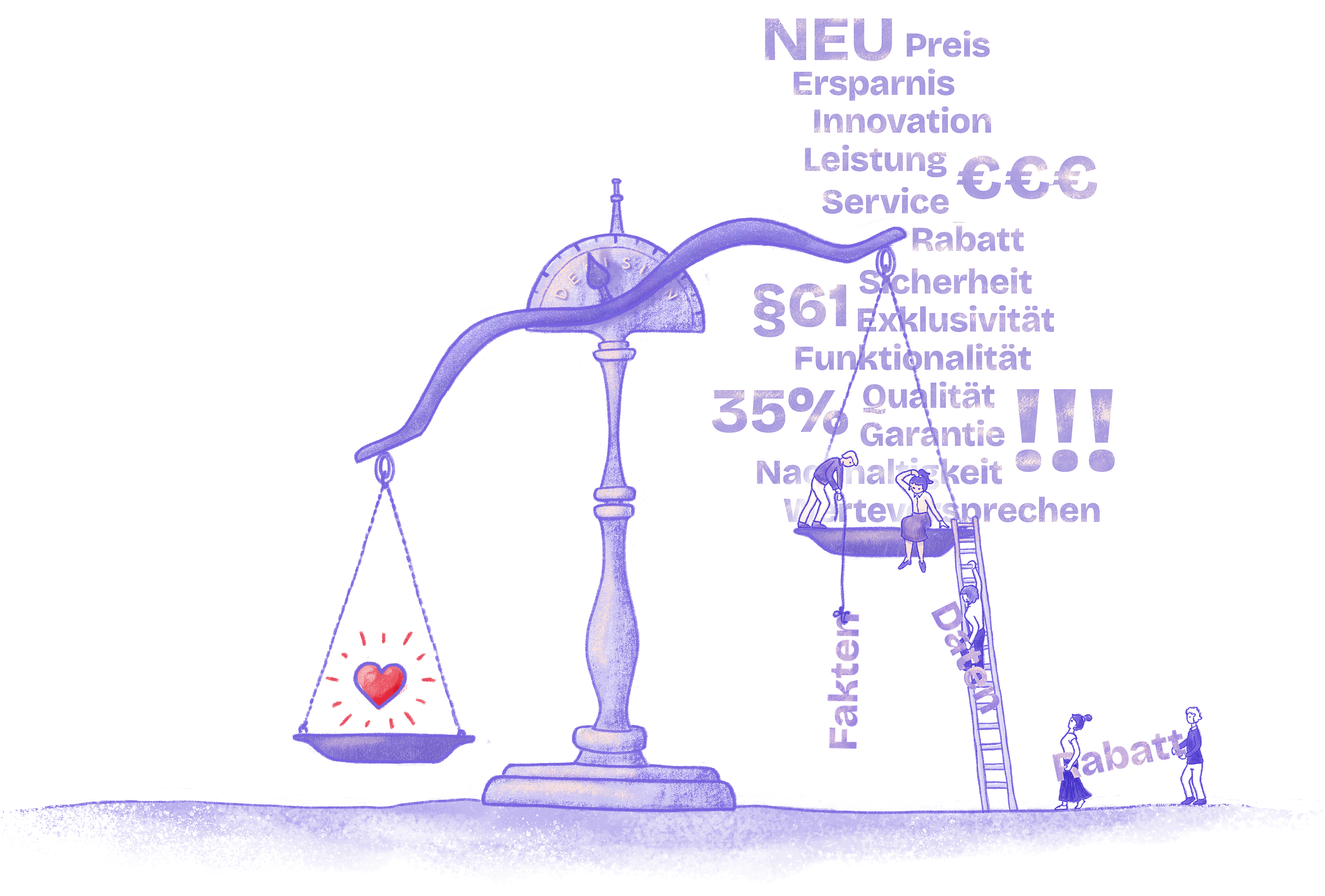

Economic rationality aims for maximum benefit: functionality, quality, price, risk, and security should deliver the highest possible value. However, the homo economicus¹—who strictly follows rational assumptions and preference orders² ³—remains a theoretical construct.

The idea of perfect rationality assumes that consumers have complete information about all decision alternatives and their consequences and that markets are fully transparent. In reality, however, consumers face incomplete data, a complex globalized world, and an unpredictable future. Time and cognitive resources are limited—an assumption known as Bounded Rationality. It is simply impossible to assess all available information and weigh every decision effectively⁴ ⁵ ⁶.

The limitation of pure rationality results from the natural constraints of information availability, processing capacity, and cognitive ability. A simple example: buying a cucumber.

"Demeter-certified from Spain—where groundwater is scarce?

Or conventional, unpackaged, but at least regional?

The shrink-wrapped organic fair-trade cucumber?

Is that certification even reliable?

Is it worth €2.99?

Which one tastes better and has more nutrients?"

Decision-making processes vary in their level of awareness and intensity depending on relevance, as illustrated by the Dual-Process Theory. Buying a house is evaluated more consciously and rationally than the quick, intuitive choice of a cucumber. Yet even this simple example shows that consumers rely on mental shortcuts and patterns to navigate the daily decision-making jungle⁷ ⁸.

Behavioral economics and consumer psychology show how needs, motivations, cognitive biases, and subconscious processes influence decisions. People tend to stick to the familiar (status quo bias), favor information that confirms their existing beliefs (confirmation bias), and fear losses more than they appreciate potential gains (loss aversion)⁹ ¹⁰ ¹¹.

A well-known social psychology model illustrating human motivation is Maslow's hierarchy of needs*. Once basic needs are met, values like security, social belonging, and self-actualization become more relevant¹² ³⁸. At these levels, consumers no longer base their choices solely on rational product attributes but assess how well a brand aligns with their inner values.

All these mechanisms shape not only purchasing decisions but also brand perception—often without consumers even realizing it. Ultimately, a company’s ability to tap into these levels determines how its offerings are perceived, even when they provide identical functionality.

How Brands Provide Guidance

If fact-based arguments alone are not enough, other ways are needed to reach people. Brands that are consistently built on values create orientation, recognition, differentiation, trust, and loyalty—for both customers and employees¹³ ¹⁴. Price sensitivity decreases¹⁵, and marketing becomes easier due to the brand’s lighthouse effect¹⁶.

Of course, this influence is not an overnight success. A clear, stable stance, continuous care, and long-term marketing and communication strategies are essential to shaping a strong brand. When done right, a brand serves as a decision heuristic¹⁶ ¹⁷—like a signpost that says, “Here, you’ll find durability, sustainability, and reliable service.”

Brands like Miele, Patagonia, or Aldi trigger associations and emotions in a matter of seconds. They offer shortcuts in the decision-making process, saving time and reducing the effort required to search for information.

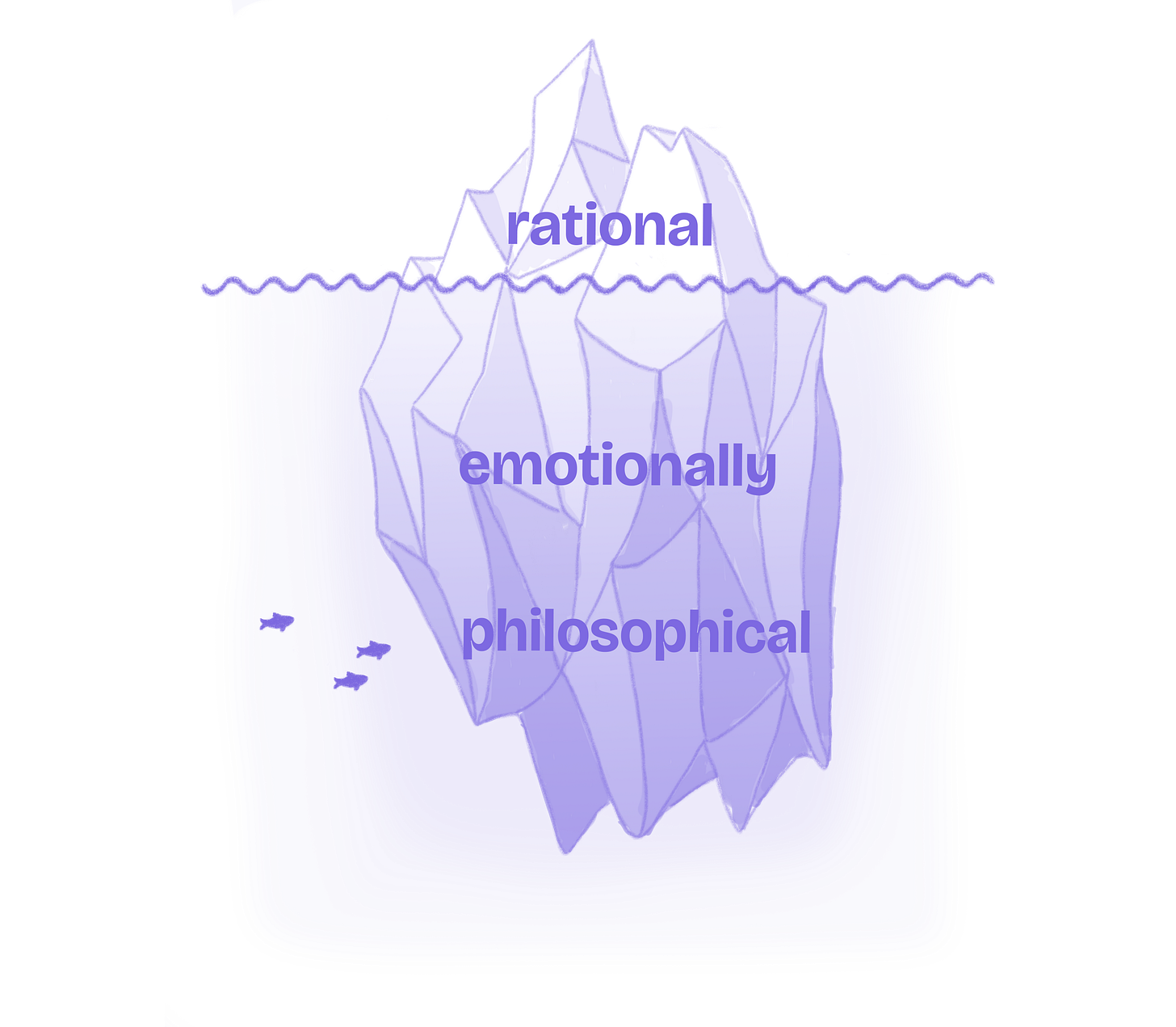

Effective brands are multidimensional. They address:

Rational aspects (functionality, quality, price)

Emotional aspects (trust, belonging, lifestyle)

Philosophical aspects (values, beliefs, worldview)¹⁶ ¹⁸

This makes strong brands meaningful and identity-forming, bringing together like-minded individuals—not just customers, but real fans and intrinsic brand ambassadors¹⁹.

Apple and Nike, for example, don’t just sell products; they provide emotions, belonging, and ideals with which people want to identify. A Tesla, a MacBook, or a Rolex tells a story of status, principles, and values:

"You are what you buy!"

Rational, Emotional, Philosophical

To understand why brand storytelling is so powerful in brand development, it is worth looking at a three-layered model of brand communication:

Rational Level (External Problem):

This level focuses on functional aspects such as quality, price, and performance. A company offers a car, a laptop, or food to meet a specific, mostly material need. This layer addresses obvious, tangible problems.Emotional Level (Internal Problem):

Behind every external need lie internal problems, feelings, insecurities, or the desire for belonging.Hipp gives parents a sense of security.

Frosch reassures eco-conscious consumers.

AutoHero eases fears of buying a used car.

Brands that connect on this level resonate with deeper human needs.

Philosophical Level (Values, Purpose):

The deepest layer concerns the meaning and values a brand represents.It is no longer just about the product itself but what owning it says about the consumer.

Porsche, Tesla, and BMW are more than just cars—they represent a way of life.

Someone choosing ChariTea over Coca-Cola signals values and a conscious stance.

People choose these brands because their philosophy resonates with their own beliefs¹⁶.

These three levels highlight the difference between mere factual communication and holistic, meaningful brand communication. Brands that engage not just with facts but also with emotions and values differentiate themselves in the market and build strong, loyal relationships²⁰ ²¹ ²².

A condensed version of this three-layered model is Simon Sinek’s Golden Circle:

*"People don’t buy what you do, people buy why you do it."*²³ ²⁴

The Narrative in Brand Development

Human communication has always been shaped by stories²⁵. People think, remember, and plan in narrative patterns²⁶ ²⁷. Narrative structures help organize complexity, make facts understandable, convey values, and connect information to everyday experiences²⁸ ²⁹ ³⁰.

Stories create meaning and significance, establish values, and provide space for identification³¹ ³² ³³ ³⁴. They activate emotions, create mental imagery, and enable intuitive understanding³⁵ ³⁶. This makes communication less effortful³⁷. On a rational, emotional, and philosophical level, stories link all relevant aspects into a clear, memorable narrative.

"A story is a sense-making mechanism!"

– Donald Miller in Story Brand

Brand storytelling harnesses these potentials, condensing companies, products, values, and visions into a coherent narrative. But the company itself is not the central focus—the customers are the heroes of their own journey.

The brand takes on the role of the wise guide, providing reliable, competent, and empathetic support.

The customer is Luke – the brand is Yoda.

The customer is Frodo – the brand is Gandalf.

This creates a deep connection, addressing needs on all levels and guiding customers toward success.

A Brand Story is not a marketing script but the core narrative that gives meaning and direction at every brand touchpoint. To be effective, it requires strategic brand management, authenticity, a clear communication strategy, and long-term maintenance.

Apple is a prime example: The brand understands the rational need (functional, reliable devices), fulfills internal needs (fun, simplicity, lifestyle), and conveys a philosophy ("Think Different") that inspires creatives. The result is a loyal community, willing to pay more than just for technical performance—because they identify with Apple’s values, vision, and narrative.

Apple doesn’t emphasize technical advantages or price-performance ratios in its communication. Instead, Apple’s Brand Story resonates consistently across every touchpoint, making it an integral part of the brand’s identity.

Using Brand Stories to Build a Strong Brand

The concepts presented here illustrate that fact-based communication alone cannot create a compelling brand world. Facts are valuable but often complex and difficult to process. Many companies don’t fail because of the quality of their products but because their communication does not align with their audience’s actual needs.

Consumers often do not immediately understand how a product improves their lives if it is presented in a purely rational and factual manner. Only the combination of rational facts, empathetic messaging, and philosophical inspiration enables truly compelling communication:

Easier purchase decisions

Stronger brand affinity

Intuitive orientation in an information-overloaded world

Brand storytelling is a key method in brand development. It embeds products and companies into a clear, relatable narrative that resonates with customers and employees alike—forming the foundation for effective brand communication.

If you want to explore brand storytelling in more depth or stay updated on branding, communication strategies, and sustainable brand communication, subscribe to my newsletter or follow me on LinkedIn or Instagram.

*At this point, I acknowledge that Maslow’s hierarchy of needs is not without criticism—particularly due to its rigid structure, its static view of needs, and its cultural bias rooted in a Western perspective. Nevertheless, I refer to this model because its familiarity and clear framework provide a useful orientation for illustrating the complexity of human motivations.

If you have feedback, comments, additional insights, or ideas, or if you need support for your project, I’d love to hear from you.

Thanks for reading Substack von LaunchPoint. Subscribe for free to receive regular insights on strategic branding and communication in the field of sustainability :

Are you looking for an expert in brand building, sustainability communication, or communication strategy? Feel free to reach out—I’d be happy to discuss how we can work together. If you’d like to learn more about me and my work, visit my website.

Sources:

1. Schäfer, HB., Ott, C. (2020). Homo Oeconomics, Behavioral Economics und Paternalismus. In: Lehrbuch der ökonomischen Analyse des Zivilrechts. Springer Gabler, Berlin, Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-46257-7_4

2. Hasse, R. & Krücken, G. (2011) Die multiple Rationalität der Organisation: Die Wirkung des Wettbewerbs. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

https://www.unilu.ch/fileadmin/fakultaeten/ksf/institute/sozsem/dok/Mitarbeitende/Hasse/Hasse_Kruecken_2011_OEkonomische_Rationalitaet.pdf

3. Smith, A. (1776/1976) An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. Edited by R.H. Campbell and A.S. Skinner. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

4. Bögenhold, D. (2015). Wider den Homo Oeconomicus: Bounded Rationality. In: Gesellschaft studieren, um Wirtschaft zu verstehen. essentials. Springer VS, Wiesbaden. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-09194-1_5

5. https://wpgs.de/fachtexte/wirtschaftspsychologie/begrenzte-rationalitaet-beispiele/

6. https://armin-wildfeuer.de/wordpress/2024/08/17/begrenzte-rationalitaet-bounded-rationality/

7. Menges, R., Thiede, M. (2023). Das ökonomische Verhaltensmodell: Rationalität und Nutzen. In: Die Ökonomie des Gemeinwohls. Springer Gabler, Wiesbaden. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-40105-4_2

8. Kahneman, D. (2012) Schnelles Denken, langsames Denken. Übersetzt von T. Schmidt. München: Siedler.

9. Schäfer, HB., Ott, C. (2020). Homo Oeconomics, Behavioral Economics und Paternalismus. In: Lehrbuch der ökonomischen Analyse des Zivilrechts. Springer Gabler, Berlin, Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-46257-7_4

10. Thaler, R.H. & Sunstein, C.R. (2008) Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness. New Haven: Yale University Press.

11. Tversky, Amos; Kahneman, Daniel (1974): Judgment under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases. In: Science, 185(4157), 1124–1131.

12. Maslow, A. H. (1943): A theory of human motivation. In: Psychological Review. Vol. 50 (4) S. 370-396.

13. „Maslowsche Bedürfnishierarchie“. In: Wikipedia – Die freie Enzyklopädie. Bearbeitungsstand: 8. Dezember 2024, 21:07 UTC. URL: https://de.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Maslowsche_Bed%C3%BCrfnishierarchie&oldid=251085443

14. https://www.pwc.de/de/handel-und-konsumguter/pwc-studie-markenvertrauen.pdf

15. Hupp, O., König, C. (2019). Markterfolg, Markenbeziehungen und Markenerlebnisse. In: Esch, FR. (eds) Handbuch Markenführung. Springer Reference Wirtschaft . Springer Gabler, Wiesbaden. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-13342-9_82

16. Hellmann, K.-U. (2005) Die Macht der Marken: Ein zentraler Mechanismus zur Orientierungshilfe beim Einkaufen. In P. Lummel & A. Deak (Hrsg.), Einkaufen! Eine Geschichte des täglichen Bedarfs. Verein der Freunde der Domäne Dahlem e. V. https://www.academia.edu/5191819/Die_Macht_der_Marken_Ein_zentraler_Mechanismus_zur_Orientierungshilfe_beim_Einkaufen

17. Baumgarth, C. (2014). Markenwirkungen. In: Markenpolitik. Springer Gabler, Wiesbaden. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-8349-4408-5_3

18. Miller, D. (2017) Building a StoryBrand: Clarify Your Message So Customers Will Listen. New York: HarperCollins Leadership.

19. Errichiello, O., Zschiesche, A. (2021). Die Marke verstehen. In: Grüne Markenführung . Springer Gabler, Wiesbaden. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-33542-7_3

20. Schmidt, H.J. (2015). Grundlagen der Markenführung. In: Markenführung. Studienwissen kompakt. Springer Gabler, Wiesbaden. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-07165-3_1

21. Esch, Franz-Rudolf (2018): Strategie und Technik der Markenführung. 9. Auflage, Vahlen Verlag.

22. Kallweit, B. (2020). Die Positionierung als Zusammenspiel zwischen Kundenorientierung, Wettbewerb und der eigenen Identität. In: Ganzheitliche Markenpositionierung. essentials. Springer Gabler, Wiesbaden. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-32510-7_2

23. Sinek, S. (2009) Start with Why: How Great Leaders Inspire Everyone to Take Action. New York: Portfolio.

24. Sinek, S. (2009) ‚How Great Leaders Inspire Action‘, TED, Available at: https://www.ted.com/talks/simon_sinek_how_great_leaders_inspire_action

25. Childs, M. C. (2008): Storytelling and urban design, Journal of Urbanism, Jg. 1, H. 2, 173–186

26. Ordu, S. (2021): Wirkungsanalyse verschiedener Content-Formate und Kommunikations-kanäle in der CSR-Kommunikation. Storytelling vs. Fakten. Wiesbaden, Heidelberg: Springer Gabler.

27. Schank, Roger C.; Abelson, Robert P. (1995): Knowledge and Memory: The Real Story. In: Advances in Social Cognition, Vol. VIII, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

28. Campbell, J. (2008) The Hero with a Thousand Faces. 3rd edn. Novato: New World Library.

29. Fisher, Walter R. (1984): Narration as a Human Communication Paradigm: The Case of Public Moral Argument. In: Communication Monographs, 51(1), 1–22.

30. Krüger F. (2017): „Corporate Storytelling – Narrative Public Relations zwischen Fakt und Fiktion“, in Schach, A. (Hrsg.): Storytelling. Geschichten in Text, Bild und Film. Wies-baden: Springer Gabler, 99 – 108

31. Espinosa, C.; Pregernig, M. & Fischer, C. (2017): Narrative und Diskurse in der Umweltpolitik: Möglichkeiten und Grenzen ihrer strategischen Nutzung. Zwischenbericht, Umweltforschungsplan des Bundesministeriums für Umwelt, Naturschutz, Bau und Reaktorsicherheit, 2017, H. 86.

32. Horn, C. (2022): Transferprotokolle. Kommunikation und Storytelling in Stadt- und Regionalentwicklung. Bielefeld: Transcript.

33. Boyd, A. & Mitchell, D. O. (Hrsg.) (2014): Beautiful Trouble. Handbuch für eine unwiderstehliche Revolution. Freiburg im Breisgau: orange-press.

34. Sammer P. (2019): „Darf man Stories Glauben schenken? – Betrachtungen zur Glaubwür-digkeit von Storytelling in Marketing, Werbung und PR“, in Ettl-Huber, S. (Hrsg.): Storytelling in Journalismus, Organisations- und Marketingkommunikation. Wiesbaden, Heidelberg: Springer VS, 171 – 196.

35. Baumgarth, C. (2014). Markenwirkungen. In: Markenpolitik. Springer Gabler, Wiesbaden. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-8349-4408-5_3

36. Adlmaier-Herbst D. & Musiolik T. (2017): „Digital Storytelling als intensives Erlebnis. Wie digitale Medien erlebnisreiche Geschichten in der Unternehmenskommunikation ermöglichen“, in Schach, A. (Hrsg.): Storytelling. Geschichten in Text, Bild und Film. Wiesbaden: Springer Gabler, 33 – 60.

37. Sammer P. (2017): „Von Hollywood lernen? Erfolgskonzepte des Corporate Storytelling“, in Schach, A. (Hrsg.): Storytelling. Geschichten in Text, Bild und Film. Wiesbaden: Springer Gabler, 13 – 32.

38. Albisser, M. (2022). Marke und Markenkommunikation. In: Brand Content und Brand Image. Springer VS, Wiesbaden. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-35711-5_2